Every monastery should have a book, and ours has just been made by Fiona Wagstaff, a maker of replica historical book who sadly has a low online presence, but she and her husband Steve can be found at re-enactors’ markets selling very cool stuff that they’ve made.

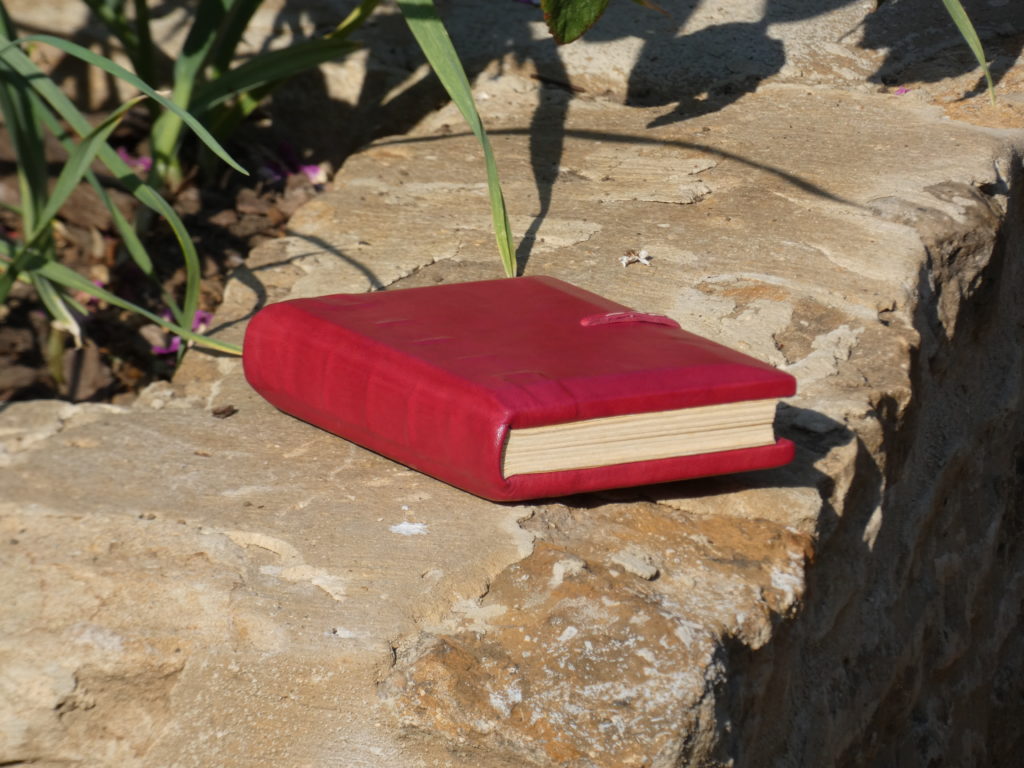

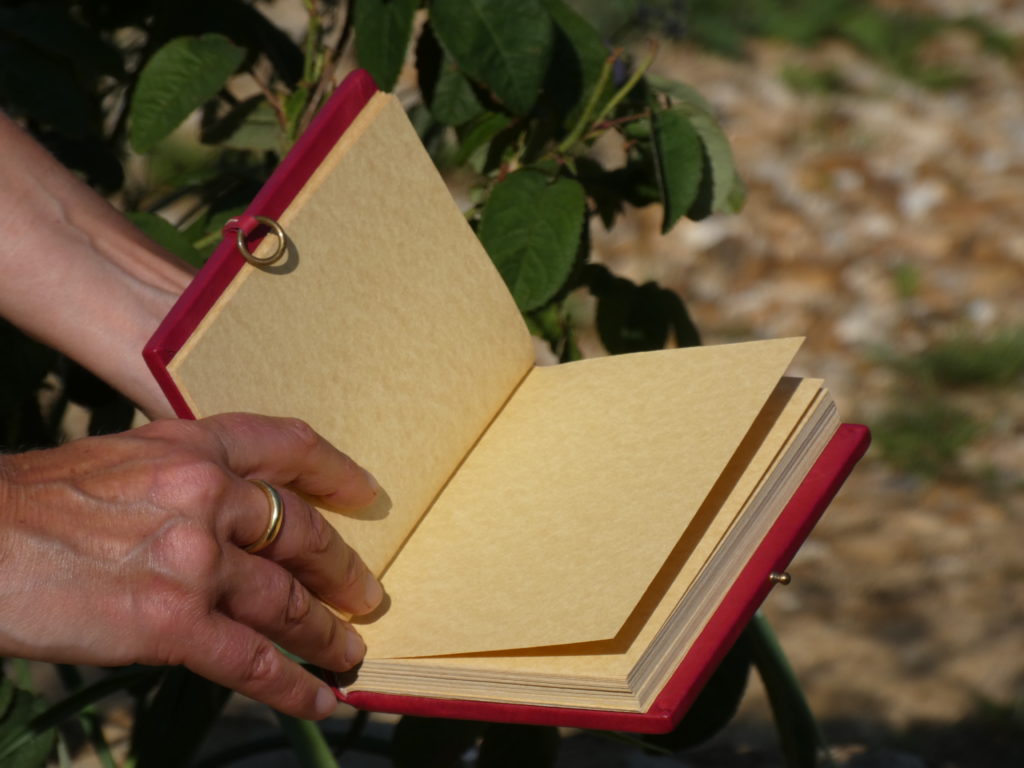

Our book is approximately 150mm x 100mm and is bound in a Coptic style as used on the St Cuthbert Gospel in the British Library, dating from the end of the 7th century. The boards are wood with an ox-blood red leather covering – and the leather is plain, because we are a relatively humble monastery. There is a ring and pin closure suitable for our 10th century date. The leaves are paper in a parchment style.

Writing in the book is of course another project. The first thing I’d like to enter is the Lord’s Prayer in Old English, and I have hopes that one of our sisters will write it using a quill pen made from feathers gathered from our neighbours’ geese. There are a number of different versions of this prayer in manuscripts and all the ones I found by web searching were composites, whereas I want to copy a single version exactly. I favour the version from the manuscript known as Cotton MS Otho C I/1 because I saw it, open at the Lord’s Prayer, in a major exhibition at the British Library in 2019. So this is the version that I have seen with my own eyes. This manuscript dates to the 1st half of the 11th century-Mid 11th century, and contains an imperfect Gospel-book, written in Old English (the so-called ‘West Saxon’ version of the Gospels). It was copied in the 1st half of the 11th century. In the mid-11th century, an Old English translation of a bull of Pope Sergius which benefitted Malmesbury Abbey was added between the Gospels of St Luke and St John (68r-69v). Decoration: Initials in red.

Here’s a link to the digitised manuscript. Use the arrow just above the top right of the scanned page to select the page with the prayer: f.38v.

The prayer starts five lines below the red star. Here is a transcription of the text:

Ure fæder þu ðe on heofone eart. si þin nama gehalgod to cume þin rice. gewurþe ðin willa on heofone ⁊ on eorþan. syle us todæg urne dæghwamlican hlaf. ⁊ forgyf us ure gyltas. swa we forgyfað ælcũ þara þe wið us agylt. ⁊ ne læd þu us on costunge. ac alys us frã yfele.

My scholarly friends inform me that the tilde above a final vowel often stands for a final ‘m’, so ælcũ stands for ælcum, and frã for fram. ⁊ is shorthand for ‘ond’, meaning ‘and’. Reference also this listing of the Anglo-Saxon latin alphabet and this article about insular hands.

Other things I’d like to add to the book over time are a short life of St Rumwold, and at least parts of a rule for the monastery, which may be in part adapted from the Rule of St Benedict for use by Anglo-Saxon women.

And Caedmon’s Hymn would be a great addition, preferably this version which has a local connection and is agreed to be West Saxon rather than the more common Northumbrian.