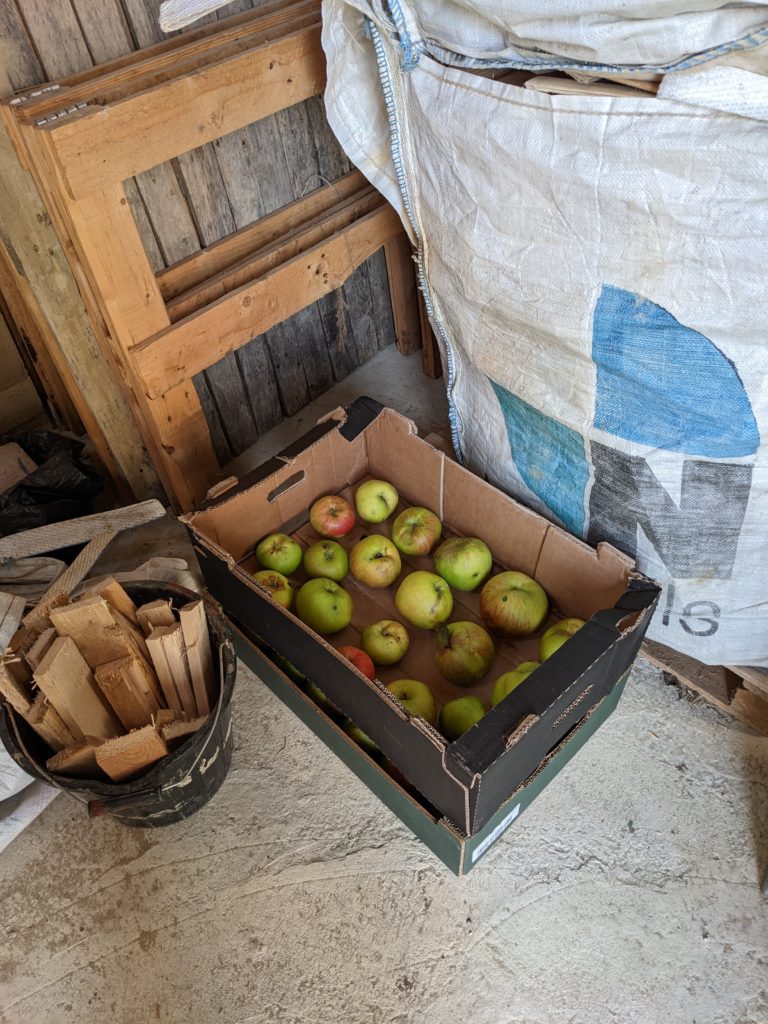

Candlemas has been and gone, marking the beginning of the end of winter, and the first signs of spring as the days lengthen. Indeed the name of the coming Christian period of fasting, Lent, derives from the Old English ‘lencten’ meaning ‘lengthen’.1 Although rats ate most of the good eating apples in the apple store – and this would be a disaster in a farming community, and we’ll have to rat-proof the store for next year – the Bramley apples proved less tempting and although there were some depredations, most were left for our use. Their keeping properties were mixed, with some surviving well and others decaying. By January they were mostly showing their age with brown fibres appearing in the flesh. On the 29th January 2023 we brought the remaining apples in to the kitchen.

Over the last week I’ve worked through them, and about one in three has eatable flesh now. If I’d been more organised I could have stewed and bottled or frozen vast amounts of good apple, but I just didn’t have the time and energy. I started eating the Bramley apples in August of 2022, as they were sharp but OK cooked, and they made excellent jelly then as they contain more pectin while unripe. So the tree has kept me in apples for about six months.

The trees now need pruning, and I have of course no idea what kind of harvest we will get this year, but I hope for a few more of the new apples, and that I’ll manage to look after the fruits better.