Among the dice and board games played by the Anglo-Saxons was the family of games commonly known by the Latin names alea [literally ‘chance’, but used to mean ‘dice’] and tabula [board]. ‘Alea, id est lusus tabulae’1 [a game of dice played on a gaming board] was played with two or three dice, twelve to fifteen counters, and a board with two rows of twelve divisions very much like a backgammon board.

Just as we play many games with a deck of cards, people would have known a number of different alea / tabula games. Our sources indicate that these were all race games in which you threw the dice, then moved your pieces according to the numbers on the dice, similar to backgammon but with significant variations.

We have evidence from classical writing, from Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, from archaeological finds and from mediaeval manuscripts.

From these sources, I propose four games that might have been played at Rumwoldstow. None of them can be proven to have been played in exactly this form, but they all derive from the source material and it is more in keeping with the character of tabula to present a number of games, than to try to insist on ‘the’ game of tabula.

An educated person will have used the Latin words alea, tabula; the word ‘alea’ came to mean any board game, not only those played with dice, as in Alea Evangelii. In Old English, tæfle meant any board game and tæflstan any gaming counter. When discussing games, people would presumably have used the name of the particular game; we do not know those names, but I have chosen names for my four games.

‘Zeno’ and ‘Pyf’ represent the two alternative interpretations of our main source for the rules, Agathias’ epigram, and are closely related to popular games in the Middle Ages. I think it very likely both games would have been played.

General principles

Roll battle to choose the starting player; each player rolls the dice and the player with the highest score plays first. Reroll if there is a tie.

On their turn, a player rolls the dice and then moves one or more of their own pieces on the board according to the numbers on the dice. The same piece may be moved several times but you cannot use a roll of two, three, six to move eleven spaces in a single bound. The moves of two, three and six must all be valid.

A ‘point’ is one of the 24 spaces on the board where pieces may be placed. Unless otherwise specified, any number of pieces belonging to the same player can occupy a point.

A ‘hit’ is when a player moves their piece to land on a point occupied by a single opposing piece; the opposing piece is removed from the board, to be re-entered on its owner’s next turn.

A point is ‘secured’ if there are two or more pieces on it, meaning the opponent cannot move a piece onto that point.

‘Bearing’ means to move your pieces off the end of the board, as in backgammon.

You may take back your move until the other player has rolled the dice for their turn.

Setup and notation

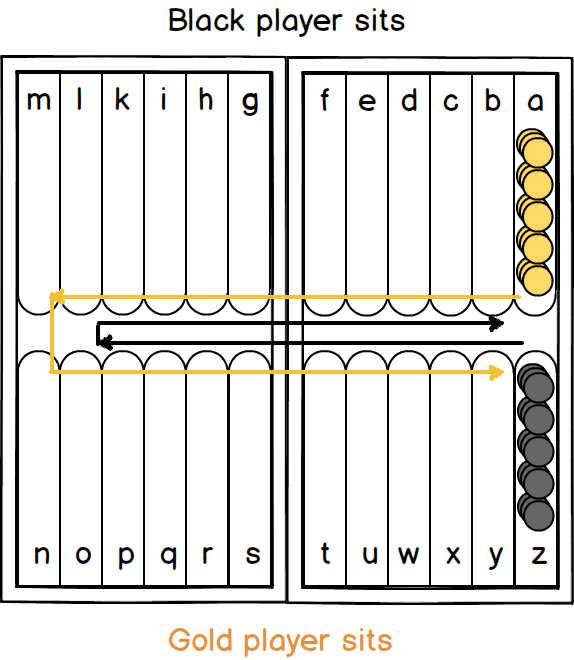

Figure 1 shows how the points on the board are labelled and where the players sit. It also shows the setup for the games where the pieces start on the board (Zeno and Ludus Anglicorum).

Zeno

Our best evidence for the rules of tabula comes from an epigram written by around 565 AD by the Greek writer Agathias describing a game played by the Byzantine emperor Zeno (425 – 491 AD). Agathias does not specify the direction of play or start position of the pieces, and writers differ in how they interpret the text; one possibility is that Agathias, writing some eighty years later, was thinking of a different game from the one Zeno was playing!

My reconstruction of Zeno’s game is a relatively simple game which can be considered a direct ancestor of the mediaeval game Ludus Anglicorum / Emperador.

Dice: 3

Setup: gold: 15 on a. Black: 15 on z. See Figure 1.

Hits: single pieces may be ‘hit’ by an opposing piece, and must be re-entered in the player’s start table before any other move may be made: af for gold, tz for black.

Movement: gold: amnz. Black: znma.

Bearing: no bearing.

Victory: the winner is the first player to move all their pieces into the furthest table from their start position: tz for gold, am for black.

Pyf

I have called this game ‘Pyf’ (Old English for ‘Puff’) after the mediaeval game ‘Buffa cortesa’ [Courtly puff]. Pyf is based on several very similar games from mediaeval manuscripts; the basic rules are those of Buffa cortesa and Pareia de entrada, and I have added the team play and restriction on movement in the bearing table from Paume Carie version 2.

Pyf is a fast-moving game with lots of interaction between the opposing pieces.

Dice: 3

Setup: all pieces start off the board.

Initial entry: pieces are brought onto table af by dice rolls, for example a roll of 1 would allow a piece to be placed on point a, a roll of 2 on point b etc.

Hits: single pieces may be ‘hit’ by an opposing piece, and must be re-entered in table af before the player move any other piece.

Movement: both players move their pieces in direction amnz. Pieces in table tz may not be moved except by bearing.

Bearing: both players bear their pieces off in table tz. Bearing is only allowed if all the player’s pieces are in table tz. A piece must be borne off by an exact roll unless there are no other pieces on more distant points. For example if the player has a piece on t and another on w, a roll of 5 may not be used to bear off the piece on w. If the player has a piece on w and no piece on t or u, they may use the 5 to bear off the piece on w.

Victory: the winner is the first player to bear off all their pieces.

Team play: teams of 2 or 3 per side may play: all the players on one side play in turn, then all the players on the other. Each player rolls two dice only.

Optional rule: any roll which a player cannot use may be used by the opponent.

Ludus Anglicorum

Ludus Anglicorum [the English game] is described in an Anglo-Norman manuscript of the fourteenth century, and the same rules appear in the thirteenth century Spanish Libro de los Juegos under the name Emperador. It is a more strategic game which appears to be an enhanced version of Zeno. I suggest that because it was so widely known in mediaeval times, and was considered by Anglo-Normans to be an English game, it may have been played in England before the Norman conquest.

Ludus Anglicorum has some special rules which encourage strategic play.

- A player may only secure points on the far side of the board from their start table.

- One of your three dice rolls MUST be a six.

Dice: roll 3 dice; if none is a six, select any one of them and turn it to be a six. Alternatively roll 2 dice and add an automatic 6 as the third dice.

Setup: gold: 15 on a. Black: 15 on z. See Figure 1.

Hits: single pieces may be ‘hit’ by an opposing piece, and must be re-entered in the player’s start table before any other move may be made: af for gold, tz for black. However a piece may only be re-entered on an empty point, or one that is occupied by a single opposing piece; this includes the player’s start point (a or z) on a roll of one.

Movement: gold: amnz. Black: znma.

Securing points: only points on the opposite side of the table from a player’s entry table may be secured, meaning that a player may never move a second piece on to any point on the side of the board where their pieces enter. A player’s starting point may be secured by their opponent; gold may place two or more pieces on z, providing black has one or fewer pieces on z. There is no limit to the number of pieces that may be placed on a secured point.

Bearing: gold bears from table tz. Black bears from table af. Bearing is only allowed if all the player’s pieces are in the bearing table. A piece must be borne off by an exact roll unless there are no other pieces on more distant points. For example if the gold player has a piece on t and another on w, a roll of 5 may not be used to bear off the piece on w, though the piece on t may be moved to z. If the gold player has a piece on w and no piece on t or u, they may use the 5 to bear off the piece on w.

Lympolding and lurching

Lympolding and lurching are strategic positions in which one player has gained a major advantage, similar to a prime in backgammon. The game will continue until one player bears off all their pieces.

Lympolding: a player is lympolded if they have a piece which must be re-entered but no available point on which to enter it, because all points in the start table are either secured by their opponent, or occupied by their own pieces. The lympolded player must skip turns until they are able to re-enter their piece.

Lurching: a player is lurched if there is no legal move because all their pieces have either reached their opponent’s start point or are within their own start table and cannot move, being trapped by a blockade of six points by their opponent. The lurched player will skip turns until their opponent opens the blockade.

Twelve dogs

Twelve Dogs is a simple teaching game and may have been played by children in the care of the monastery.

The game is played on one table only, and the goal is to enter all your pieces on the board. There is no movement, but singletons can be taken and must re-enter. Twelve dogs seems to be on a level with snakes and ladders in that the player makes no decisions, just moves their pieces according to the dice.

Dice: 2

Setup: all pieces start off the board. The player who is to play first chooses the table which is to be used for the game.

Entry: pieces are brought onto table af by dice rolls, for example a roll of 1 would allow a piece to be placed on point a, a roll of 2 on point b etc. Players enter their pieces in the same direction. Each point may have a maximum of two pieces.

Hits: single pieces may be ‘hit’ by an opposing piece, and must be re-entered in table af before the player can play any other pieces.

Movement: no movement.

Bearing: no bearing.

Victory: the game ends when there are two pieces on each of the six points of the table. The winner is the player who has occupied the most points; the game may be tied.

References

My article ‘Tabula at Rumwoldstow’ contains a full discussion of the sources and reasoning which led to the four games presented on this page, and references to the source material.

Becq de Fouquières wrote an extensive and widely-quoted analysis of the Game of Twelve Lines and tabula in antiquity. His original text is available here. As it is in French, and out of copyright, I have run it through a popular online translation service and cleaned it up a little, enabling English-speaking readers to check the basic sense of his arguments and references. You can read Becq de Fouquières in English here.